Let’s go down memory lane and walk through our paths of blissful oblivion. Childhood. Does it remind you of happy laughs and innocent tears? Does it resemble your happy place? “Obviously,” may be your response.

Not every child has experienced their right to this obvious.

According to a report published by UNICEF in 2016, 200 million girls and women alive then, had been subjected to Female Genital Mutilation. Girls, who were fourteen years or younger, represented 44 million of those who had been cut.

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) refers to the practice of partial or total removal of external female genitalia for non-medical purposes. Depending on the extent to which a girl’s external genitalia is mauled, FGM is classified into four types:

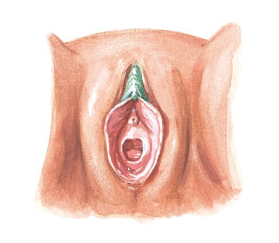

- Type 1 FGM: Clitoridectomy

This involves the partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals), and in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris).

Source: “Types of FGM.” Daughters of Eve

2. Type 2 FGM: Excision

This involves the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without excision of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva ).

Source:“Types of FGM.” Daughters of Eve

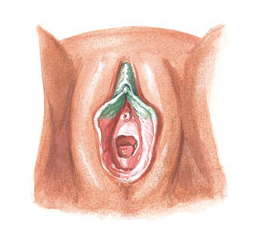

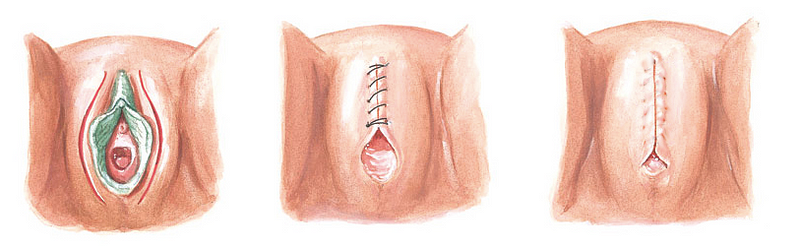

3. Type 3 FGM: Infibulation

This involves the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy).

Source: “Types of FGM.” Daughters of Eve

4. Type 4 FGM

This includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterising the genital area.

Unfortunately, these descriptions don’t do justice to the horrors of FGM. Imagine a week old baby girl, still learning to breathe outside her mother’s womb, still so feeble and vulnerable — a small prick hurts her tender skin so much, she could cry for hours. She is unaware and helpless.

Women from the community, with a razor, without anaesthesia, brutally cut pieces of her genitalia, even before it has developed. She is left bleeding and crying.

According to statistics published by UNICEF, 85% of the girls in Yemen were cut in the first week of their lives between 2010 and 2015.

According to research conducted by UNICEF, as of 2015, FGM is found to be concentrated in African countries, with its prevalence being the highest in Somalia, where 98% of the women have been circumcised. Furthermore, it is also ingrained in some communities of Middle Eastern countries like Yemen and Iraq and in Asian countries like Indonesia. Although concrete statistics are not available, it is a widely recognised claim that FGM has crept into Europe, Australia and The United States of America, which have been abodes for migrants from countries where FGM is practised widely.

The prevalence of FGM insinuates the prevalence of gender inequality. It is without a doubt gender inequality incarnate, and is so in a devastating form. The idea that the virginity of a woman is the measure of her worth and measure of her family’s honour is one that is etched into the fabric of various communities around the world, and to such an extent that it gave birth to the need to control and limit the sexuality of women. FGM devoids a woman of her right to sexual pleasure by making sex extremely painful for her. In communities where this practice is rampant, circumcision is often deemed as a symbol of a woman’s purity and is often a quintessential condition for marriage. Since women in these communities are economically vulnerable, they depend on their male counterparts for a living, which makes marriage a very essential alliance for them — both for finances and also, for an identity.

In her TEDx talk, ‘Born a girl in the wrong place’, Khadija Gbla explains how her community celebrated her circumcision as a festival, as a ceremony that would transform her into an adult. Often, drums are played during circumcision so that the girl’s screeching and crying go unheard.

The sad fact remains that most of these communities do not acknowledge FGM as a crime and instead believe that being born a girl implies that the child deserves circumcision. Further, the women who have undergone the trauma are the ones who believe that their children deserve the same. Because they believe that the tradition is essential to maintain the ‘purity’ of their daughters, they don’t hesitate to accept this. Among communities where FGM has been practiced as a tradition, it is absolutely normal for women to undergo the pain so much so that the communities are often desensitised towards the painful screeches of the young girls and often, they even take pride in the act of circumcision. Yo Fane, who boasts about being Mali’s most sought-after practitioner of FGM, proudly claims that she ‘chops’ 200 girls every month. Without any hesitation, she claims “I spread their legs and hold the clitoris between my two fingers and cut the tip of it and it’s all over in a jiffy.” It’s as simple as that!

The horrific reality is that FGM is extremely painful. Assia, now 29, describes the gut-wrenching pain of being circumcised at the age of 6 — “The pain is, well, it’s so difficult to describe to you what it is like. Imagine when you cut your finger, it’s a million times worse than that. But that doesn’t even begin to describe the type of pain that takes over when the part of your body that has the most nerve endings in it is cut away. Only girls who have been cut will ever know what that level of pain is like. I honestly thought I was going to die, and then everything went black.” Often, girls succumb to death after being cut because excision of the clitoris involves cutting across the high-pressure clitoral artery which may lead to incessant bleeding. Extensive bleeding can lead to hemorrhagic shock and in some cases, sudden death. Another immediate consequence of FGM includes fractures of the clavicle, femur, humerus or hip joint if too much pressure is applied by multiple adults who hold the girl down as she struggles in pain during circumcision.

Unfortunately, this is just the tip of the iceberg. FGM has consequences which haunt its victims for the rest of their lives. FGM results in girls being vulnerable to urinary infections and formation of keloids on their wounds. Further, menstruation is agonising for girls who are cut because the narrower outlet for menstrual blood leads to inflammation of internal sexual organs. It also leads to dyspareunia i.e. painful sexual intercourse and also results in multiple complications during childbirth, leading to a greater probability of maternal and foetal mortality. These detrimental consequences are worse for women who have been infibulated (Type 4 FGM) because the stitchings on their genitalia require cutting and stitching several times which intensifies the pain and makes them more prone to the harmful medical consequences.

Furthermore, when girls are circumcised, they are too young to understand that they are being mutilated. Since it is the norm in their communities, they never realise that they are victims of FGM until they step out of their communities and interact with women who haven’t been cut. Mariam Doumbia, a 23-year-old victim of FGM said, “I thought it was how virgins looked.” When the knowledge and realisation of having been mutilated finally dawns upon the victims of FGM, the damage is irreversible. Knowing that they too have the right to a clitoris and to sexual pleasure, they often suffer from depression and low self-esteem.

“It is what my grandmother called the three feminine sorrows: the day of circumcision, the wedding night and the birth of a baby.” These words from a Somali poem ‘The Three Feminine Sorrows,’ portray a clear picture of the abominable state of women who have been circumcised. Generation after generation, decade after decade, women have been denied their right to a clitoris. It’s time we realise that the laws alone won’t dissuade the practitioners from inflicting this pain on their daughters. It’s time we realise that this practice has no religion and it doesn’t recognise barbed fenced borders. It’s time we realise that FGM is not a feminine issue — it’s a violation of human rights. After all, it’s women who do it to women because they have been nurtured with the idea that their vagina is ‘dirty’, that virginity is purity, and that sexual desires are filthy. It’s time to empower women, to make them realise that like men, they too have the right to sexual pleasure; that there is nothing wrong about having a sexual drive; that their mutilated genitalia doesn’t have to carry the weight of their family’s honour.

Sara Sethia is a Research Associate (Gender Justice) at One Future Collective.